Keys and passwords in Heads

There are “too many secrets” involved in booting a Heads system. Luckily most of them are stored in hardware and only a few need to be memorized by the users. This page documents their usage and the risks if an attacker can compromise the different keys.

Table of contents

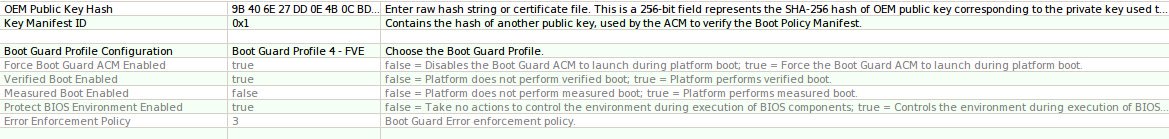

Management Engine and Bootguard ACM fuses

The very first key used in the system is Intel’s public key that signs the Management Engine firmware partition table in the SPI flash. This key is stored in the on-die ROM of the ME and the ME will not start up if this signature does not match. An attacker who controls this key (which is highly unlikely) can subvert the Bootguard checks as well as the measured boot process.

The Bootguard fuses fuses provide protection against most “evil maid” attacks against the firmware. The hash of the ACM signing key is set in write-once fuses in the CPU chipset and during the CPU bringup phase the ME and the CPU microcode cooperate in some undocumented way to validate the “Startup ACM” in the SPI flash. Since this key is fused into hardware, an evil maid attack would need to replace the CPU to install malicious firmware into the SPI flash. The x230 Thinkpads do not support bootguard and only the Librem laptops ship with unfused keys.

An attacker who controls this key can flash new firmware via hardware means (and possibly remotely via software, unless other steps are taken).

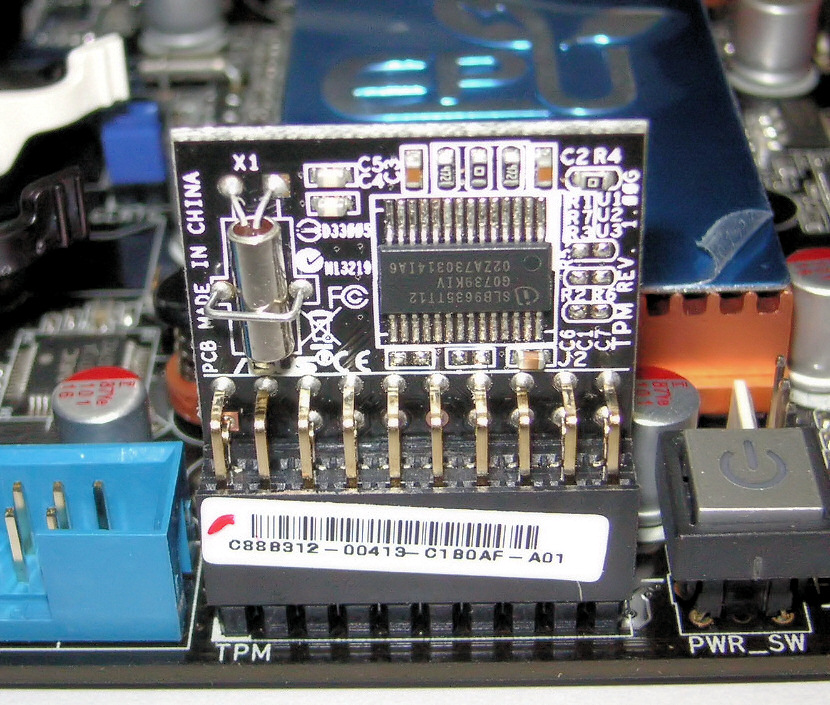

TPM Owner password

As part of setting up Heads, the TPM is “owned” by the user and the owner password is set. This clears all existing NVRAM and spaces.

An attacker who controls this key can reseal TPMTOTP shared secret.

TPMTOTP shared secret

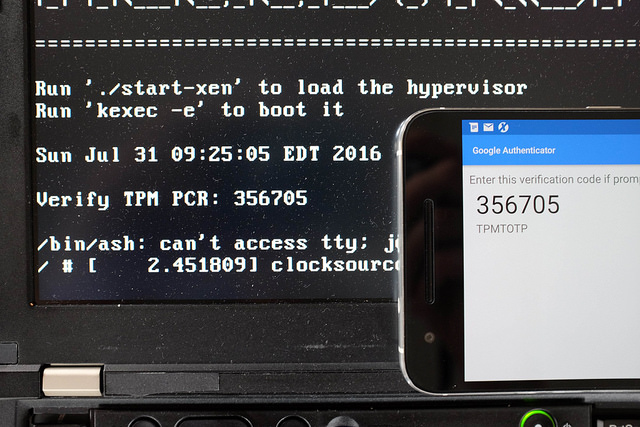

Since humans have trouble doing RSA public key cryptography in their brains, Heads uses TPM TOTP to let the system attest to the user that the firmware is unmodified. During setup, a random 20-byte value is generated and shared (via QR code) to the user’s phone and sealed with the correct TPM PCR values into the TPM NVRAM. On subsequent boots, the TPM will unseal the secret if the PCRs match, and the computer generates a one-time password based on the current clock time, which the user can compare to the value displayed on their phone. A new secret must be generated each time the firmware is updated since this will change the PCRs.

Note: Heads generates TPMTOTP codes that appear on your screen. You compare these with codes from your phone’s authenticator app to verify firmware integrity. This works independently of your USB Security dongle. Critical requirement: You must manually set the correct time in Heads through the Options menu (UTC/GMT timezone) - if the time doesn’t match your phone, verification will fail.

If an attacker can control this shared secret (such as by directly sending PCR values into the TPM), they can install malicious firmware in the SPI flash and generate valid TOTP codes.

TPM counter key

The TPM’s increment-only counters can be used to prevent roll-back attacks on the signed kernel and initramfs configurations. An attacker who controls this key can increment the counter, causing a denial of service attack against the system, but it does not provide access to encrypted data nor any way to roll back to an old version.

TPM Disk Unlock key

The TPM NVRAM stores one of the disk encryption keys, which is encrypted with the user’s Disk Unlock Key passphrase and sealed with the TPM PCR values for the firmware and the LUKS headers of the disk. On every boot, the user types in their TPM Disk Unlock Key passphrase and the TPM will unseal and decrypt the disk encryption key if the firmware is unmodified and the passphrase matches. Since the TPMTOTP one-time code matched, the user can have confidence that the firmware is unmodified before they enter their TPM Disk Unlock Key passphrase. If the system is booted in recovery mode, the PCRs will not match and this key is not accessible to the user.

The Heads firmware inserts this key into the Qubes initramfs.cpio as /secret.key, which is listed in the /etc/crypttab file as the decryption key for the various partitions. The dracut/systemd startup scripts will read the /etc/crypttab file and use it to decrypt the drives without further user intervention.

The sealed blob is not secret since it is both encrypted and sealed, but if an attacker can extract this unsealed and decrypted key, they can decrypt the data on the disk. If they extract the TPM, they can set the PCRs to the correct values and attempt to brute force the unlock code, although the TPM should provide some rate limiting. TODO: Can the TPM also flush the keys if too many attempts are made?

Disk Recovery Key

During initial system setup, the disk is encrypted with a user-chosen passphrase. When a TPM Disk Unlock Key is set up, this key is only entered if the TPM PCRs have changed, such as following a firmware update, or if the disk has been moved to a new machine and the user needs to back up the code. If the system is booted into recovery mode, the TPM PCRs will not match the TPM sealed Disk Unlock Key, so the user will need to enter the recovery key to decrypt the drives.

If an attacker gains control of this recovery key, they can decrypt the disk to access the data, but not necessarily the system configuration if dm-verity is configured. They can also add additional disk decryption keys, although this will be detected by the TPM measurement of the LUKS headers.

LUKS Keys and Passphrases

The TPM Disk Unlock and user’s Disk Recovery passphrases are not the actual encryption keys for the disk. These passphrases are processed through PBKDF2 (LUKS1) or [Argon2] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argon2) (LUKS2) to derive a key. This derived key then decrypts the actual disk encryption key stored in the LUKS header.

The disk encryption key itself remains hidden from users, serving only as an implementation detail for the encryption process.

Owner’s GPG key

The owner of the machine generates a GPG key pair as part of installing Heads. Ideally, the private key does not live on the machine, but instead is in a Yubikey or other USB Security dongle.

The security dongle may be used in the disk decryption process. Some of the Linux distros have incorporated this using /etc/crypttab with a keyscript option.

An attacker who controls this private key can replace executables in /boot and if they also control the disk encryption key, they can tamper with files in a dm-verity protected root filesystem.

User login password

The user’s login password is used to control access to the system once it has booted.

An attacker who controls this key can access the system and the decrypted disks if they gain physical access to the system while it is running or asleep. This provides access to the data on the drive, but not necessarily the ability to modify a dm-verity protected root filesystem.

Root password

The root password is not enabled by default on Qubes, so it is functionally equivalent to the login password. Other operating systems might differ.

TPM PCRs

0: Nothing for the moment (Populated by binary blobs where applicable for SRTM)

1: Nothing for the moment

2: coreboot’s Boot block, ROM stage, RAM stage, Payload (Heads linux kernel and initrd)

3: Nothing for the moment

4: Boot mode (0 during /init, then recovery or normal-boot)

5: Heads Linux kernel modules

6: Drive LUKS headers

7: Heads user-specific files stored in CBFS (config.user, GPG keyring, etc).

(16): Used for TPM futurecalc of LUKS header when setting up a TPM disk encryption key

Some history

Heads relied on coreboot patches until coreboot 4.8.1 for measured boot implementation, since coreboot had none. Heads measured boot scheme changed to match coreboot 4.12’s, which for the first time included separated measured boot implementation from vboot implementation.

Since coreboot 4.12, Heads stopped patching coreboot to implement measured boot. coreboot measured boot implementation is the one filling PCR2, above.

Heads since then solely extends PCRs of its own (PCRs 4-5-6-7 above) which are used when sealing/unsealing.

As you can see above, coreboot measures itself from bootblock then other boot phases up to its payload in PCR2, in conformity of their SRTM measured boot policy. An example is given from coreboot docs.

TPM_Unseal errors

Consequently, if either coreboot phases, boot mode, kernel modules, LUKS headers or CBFS files are different then when those measurements were used to seal secrets, unseal operations will fail. HOTP/TOTP/TPM Disk Unlock Key passphrase should give errors in case of tampering.

The TPM Disk Unlock Key passphrase would fail with a different error then: Error Authentication failed (Incorrect Password) from TPM_Unseal when a user types a TPM Disk Unlock key passphrase.

Indeed, the PCRs measurements used to seal the Disk Unlock Key in TPM NV memory cannot unseal that secret, even with a good TPM Disk Unlock Key passphrase, while HOTP/TOTP should not be able to unseal either.

TCPA Event log

From the Recovery Shell, it is possible to review PCR2 TCPA event log by typing: cbmem -L

Disk Unlock Key passphrase prompt output

Here you can see that “Boot block, ROM stage, RAM stage, Heads payload”, “Drive LUKS headers” and “Heads user-specific config files” have filled the registers PCR-02, PCR-06 and PCR-07 respectively. You can also see the TPM returning the error “Error Authentication failed (Incorrect Password)” which is an invitation to try again, this time typing more slowly. Measurements are consistent to what was sealed, but the passphrase is bad. This is good news.

After 3 unsuccessful attempts releasing TPM Disk Unlock Key, Heads will propose you to decrypt with your Disk Recovery Key passphrase, directly from the OS, bypassing Heads protection. Still good news.

If Disk Unlock Key passphrase throws a different error, it would be a good idea to meditate on your threat model and what happened to your computer since your last normal default boot.

The Disk Unlock Key is sealed in TPM NV memory with PCRs-2-4-5-6-7, which includes external content from the firmware, like your LUKS header measurements.